June 28, 2017

by Doug “Uncola” Lynn:

Today, across the globe, there remains a clash of cultures as ancient as religion; as violent as tides crashing upon the shores of nations; islands separated within seas of humanity. Ongoing wars rage on in the middle-east as democracies fight theocracy, and waves of Islamic immigrants flood onto the shores of western nations like tsunamis. Although oil and water will not mix well, there are those who perennially hope to try; and, if history serves as any right measure, the blending will continue to roil and boil like ships on fire in perilous ports.

Will the captains in the Western nations lead us safely on our journey? I think not. To know where we’re going, we must first understand where we are, and where we’ve been.

Seven years ago, Prince Charles, the future head of the Church of England (if he succeeds the throne), urged the world to embrace Islam in order to save the environment. According to the Pew Research Center, Muslims are expected to make up eight percent of Europe’s population by 2030, and a 2016 survey has revealed the majority of respondents within the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Sweden, and the Netherlands view Muslims favorably.

According to the Gatestone Institute, 500 Christian churches have been closed in London, as 423 new mosques were established there, since 2001; The Independent reported that the number of Briton’s converting to Islam had doubled in the 10 years following 911; and, in 2015, the most popular baby name in England was Mohammed.

Across the pond, here in America, near one-third of those responding to a 2015 CNN Poll believed President Obama was a secret Muslim. It is a fact, on many occasions during his presidency, Obama, at the very least, expressed extreme sympathy for Muslims, ranging from his greatly exaggerated claims of Islamic contributions to American society; to stating at the United Nations how “the future must not belong to those who slander the Prophet of Islam”; to his appointment of Muslims to influential government positions; his pro-Islamic immigration policies; his release of top-tier terror operatives from Guantanamo, and his persistent unwillingness to name radical Islam as behind every terror attack where shouts of Allahu Akbar were heard amidst the painful screams of bleeding infidels from near every nation on earth.

Oddly enough, in American schools, on college campuses, and all throughout the political left today, Islamic society is viewed with great sympathy and compassion, in spite of the extreme intolerance as mandated, and demonstrated, under Sharia law. Furthermore, in every instance of Islamic terrorism, our politicians and media unceasingly remind us how these are not representative of Muslims in general, or the Islamic faith, of which they claim is a religion of peace.

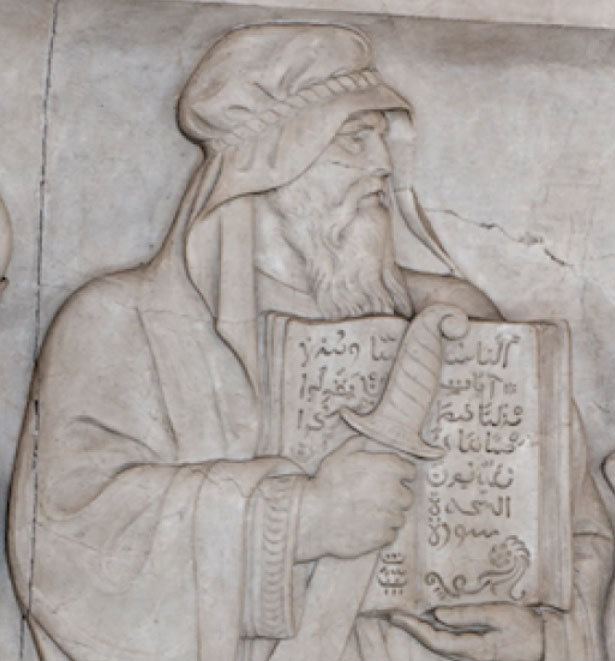

Now the Supreme Court has recently agreed to rule on President Trump’s so-called “Islamic Travel Ban” this fall. Ironically, on the North Wall Frieze of the courtroom above where the nine Supreme Justices sit, there is a depiction of Muhammad holding a Koran with his left hand, and a sword in his right hand. Did you know that a Spanish marble sculpture of the Prophet of Islam was chosen, along with seventeen other historical lawgivers, to reside over the Supreme Court Justices as they interpret and rule according to the United States Constitution?

Many moons ago, I remember watching Oliver North being interviewed on television about middle-eastern affairs; and, while addressing Islam, he mentioned a book entitled “Sufferings in Africa” by James Riley. It is an 1817 non-fiction memoir written by Riley, a ship’s captain, who was taken into slavery by “African Mohammedans” after a shipwreck off the coast of the Western Sahara in 1815. As I recall, North said he read the narrative as a young Marine and that it was, at one time, required reading in the U.S. military academies.

I wrote down the name of the book, found it several years ago, read it, and enjoyed the tale very much. I especially appreciated the honest insights into the “Mohammedan mind” and later became fascinated by the story’s overall relevance through time. Recently, and upon reading an internet post that made mention of Barbary Pirates, I was inspired to revisit “Sufferings in Africa” once again. Because I couldn’t find my original book, I downloaded it to my phone and re-read it last week while on vacation, paradoxically, to the sounds of the surf rolling in upon the sugar-white sands adorning the shores of the very same sea where Riley began his journey, the very same week in June, exactly 202 years ago.

When originally published in 1817, the book was titled “An Authentic Narrative of the Loss of the American Brig Commerce”. President Abraham Lincoln listed the story, along with The Bible and The Pilgram’s Progress as among the most influential works shaping his political ideology; his views on slavery in particular. Unsurprisingly, after his harrowing experiences, the author, James Riley, became an ardent abolitionist. And, Riley’s terrifying tale is said to have influenced James Fennimore Cooper and Henry David Thoreau as well.

Just sit right back and you’ll hear a tale,

A tale of a fateful trip

That started from a Gulf seaport

Aboard a sailing ship

James Riley was born in Middletown, Connecticut in 1777. Due to a lack of money, his father arranged for young James to work on neighboring farms from the age of eight through his fourteenth year. By the age fifteen, however, Riley was tired of farm work and decided the best way to “get rid of it” was to go sea and visit foreign lands. After obtaining the reluctant consent of his parents, he was soon bound for the West Indies. By age twenty, Riley had “passed through the grades” of cabin boy, cook, ordinary seaman, seaman, second mate and chief mate on various vessels. Upon becoming a captain, he had learned to read, write, and speak both the French and Spanish languages; he witnessed “many important operations in the science of war”; and he took “lessons in the school of adversity” which he said prepared and disciplined him for hard times.

On June 24, 1815 the Brig Commerce (originally of Harford, Connecticut) sailed from the port of New Orleans with cargo consisting of tobacco and flour, towards Gibraltar and arriving there on the ninth of August. Taking aboard a cargo of brandies, wines and about two-thousand dollars, the crew set sail again on the twenty-third of August, intending to pick up a load of salt by way of the Cape de Verd islands. Due to extreme fog, however, they veered off course and became trapped in a current that caused them to strike breakers positioned in the violent waters just off the coast of western Africa.

In very short while, Captain Riley and the crew of the brig Commerce were confronted on the beach by fierce and bold native thieves whom Riley believed to be cannibals. Through greed, trickery, treachery, and violence, the savages ended up killing one of the crew members as Riley made a daring escape by running, then swimming, for his very life until he reached the rest of his crew rowing in a severely damaged longboat back to the wrecked main ship. Upon reaching the main boat, Riley, realized their only way to escape the murderous natives on the shore, would be to row out to sea in the tremendously impaired longboat. Seeing no other choice, the men grabbed what sparse provisions they could from the marooned Commerce and considered the twenty-foot swells they were soon to face:

Every one trembled with dreadful apprehensions, and each imagined that the moment we ventured past the [shipwrecked] vessel’s stern, would be his last. I then said, ‘let us pull off our hats, my shipmates and companions in distress.’ This was done in an instant; when lifting my eyes and my soul towards heaven, I exclaimed, ‘great Creator and preserver of the universe, who now seest our distresses; we pray to thee to spare our lives, and permit us to pass through this overwhelming surf to the open sea; but if we are doomed to perish, thy will be done; we commit our souls to the mercy of thee our God, who gave them: and Oh! universal Father, protect and preserve our widows and children.’

Riley, James. (1817). “Sufferings in Africa”, Skyhorse Publishing, 2007, Chapter VI

Although Riley was advised to leave out this portion of the story for fear of some doubting his entire narrative as a result; in his Note to Readers at the beginning of his book, the author said he was “adamant” to leave it in exactly as it happened out of “holy gratitude” for the “infinite goodness” of his “divine Creator and Preserver” for what happened next:

The wind, as if by divine command, at this very moment ceased to blow. We hauled the boat out; the dreadful surges that were nearly bursting upon us, suddenly subsided, making a path for our boat about twenty yards wide, through which we rowed her out as smoothly as if she had been on a river in a calm, whilst on each side of us, and not more than ten yards distant, the surf continued to break twenty feet high, and with unabated fury. We had to row nearly a mile in this manner; all were fully convinced that were saved by the immediate interposition of divine Providence in this particular instance, and all joined in returning thanks to the Supreme Being for this mercy. As soon as we reached the open sea, and had gained some distance from the wreck, we observed the surf rolling behind us with the same force as it had on each side of the boat.

Riley, “Sufferings in Africa”, Chapter VI

This instance of apparent divine Providence, along with a later, very vivid, dream promising deliverance from his forthcoming and brutal slavery by the followers of Mohammed, both gave Captain Riley the faith to not only persevere, but to continually encourage his shipmates as well, in the face of what seemed impossible odds for survival.

After nine days of rowing and constantly bailing at sea, the long-boat, severely battered, and their provisions all but gone, the extremely sunburned and exceedingly famished crew, once again, rowed to shore and were nearly smashed to bits upon jagged rocks beneath the steep cliffs of the West African coast; except for a strong wave that carried them up and over, thus landing them safely onto a small beach area.

Upon climbing the coastal cliffs while suffering from severe dehydration and exhaustion, the tattered crew soon saw the fires of nomadic Arabs who later discovered them, stripped them naked, and made them all slaves. This is when things became really dire for Captain Riley and the crew of the lost brig Commerce.

For the Arabs set no bounds to their anger and resentment, and regard no law but that of superior force.

Riley, “Sufferings in Africa”, Chapter XV

It is not in the purview of this essay to retell Riley’s entire story of survival, but I will say I found it to be a fantastic description of hardship, adventure, faith, kindness, cruelty, intrigue, coincidence, luck, and wonderment. Above all, the perspectives on human nature, and the insights into those of the Islamic faith, especially, were invaluable.

Speaking of Arab men, Riley wrote:

They are the lords and masters in their families, and are very severe and cruel to their wives, whom they treat as mere necessary slaves, and they do not allow them even as much liberty as they grant to their negroes, either in speech or action they are considered by the men as beings without souls, and consequently, they are not permitted to join in their devotions, but are kept constantly drudging at something or other, and are seldom allowed to speak when men are conversing together.

The Arab is high-spirited, brave, avaricious, rapacious, revengeful; and, strange as it may appear, is at the same time hospitable and compassionate: he is proud of being able to maintain his independence though on a dreary desart, and despises those who are so mean and degraded as to submit to any government but that of the Most High. He struts about sole master of what wealth he possesses, always ready to defend it, and believes himself the happiest of men, and the most learned also; handing down the tradition of his ancestors, as he is persuaded, for thousands of years. He looks upon all other men to be vile….

Riley, “Sufferings in Africa”, Chapter XXVI

Strangely enough, the Mohammedans in Riley’s tale were portrayed as both cruel tormentors and as being overtly hospitable, and helpful, at the same time. In fact, there were some Arabs who treated Riley as mere merchandise, and others who were directly responsible in securing his freedom, as well as the liberty of four remaining members of Riley’s crew; albeit for a ransom of $920 and two double-barreled shotguns paid by an Englishman named William Willshire, who now has a city in Connecticut named after him thanks to the ensuing, post-ordeal, efforts of Captain James Riley.

so true it is that the most generous and humane men are always the most courageous.

Riley, “Sufferings in Africa”, Chapter XVI

Because of similarities between the Arabic and Spanish languages, Riley was able to negotiate his transport across the Sahara under the auspices of an Arab by the name of Sidi Hamet, who proved to be Riley’s trusted benefactor in the end. However, Sidi’s own brother, Seid, wished to be rid of Riley and his shipmates, at every turn; even conspiring against Riley’s efforts toward freedom with Shieck Ali, who was Sidi Hamet’s charismatic, conniving, and powerful father-in-law.

Actually, some of my favorite exchanges in the book occurred between a Moor by the name of Rais Bel Cossim (a trusted friend of William Willshire, who paid Riley’s ransom), and the treacherous Sheick Ali who attempted, repeatedly, to thwart Sidi Hamet’s efforts to secure Captain Riley’s release.

At one point, Rais Bel Cossim said to Captain Riley:

You have indeed been preserved most wonderfully by the protection and assistance of an overruling Providence, and must be a particular favorite of heaven: there never was an instance of a Christian’s passing the great desart for such a distance before, and you are no doubt destined to do some great good in the world; and may the Almighty continue to preserve you, and restore you to your distressed family. Sidi Hamet admired your conduct, courage, and intelligence and says they are more than human – that God is with you in all your transactions, and has blessed him for your sake.

Riley, “Sufferings in Africa”, Chapter XX

Yet, in an effort to circumvent the charismatic, double-crossing, Shieck Ali, it was the same Rais Bel Cossim who placated the former, whom he had never met before, by stating the following regarding the shipwrecked prisoners:

We are of the same religion and owe these Christian dogs nothing; we have an undoubted right to make merchandise of them, and oblige them to carry our burdens like camels.

Riley, “Sufferings in Africa”, Chapter XX

Indeed, just as many of their descendants today, the Mohammedans of the early nineteenth-century did not have much love for the Christian men of the West:

A great many men, and I believe, all the boys belonging to the place, now came out to look at and make remarks on the slaves; most of them, no doubt from mere curiosity. The boys, by way of amusement, began to throw stones and dirt at, and to spit on us, expressing, by that means, the utter contempt and abhorrence of us and of our nation.

Riley, “Sufferings in Africa”, Chapter XXI

Moreover, also like the modern followers of Islam, the Muslim Forefathers of Old did not show much love even for those of their own blood. Upon observing an area where several cities were abandoned due to a war that was started by a family quarrel between the chiefs of two towns, Riley wrote:

…their environs laid desolate, though the war continued only one month. I could scarcely believe it possible for such devastation to have been committed in so short a time or on such trivial grounds; but Rais bel Cossim (who was born near Santa Cruz) assured me that nothing was more common than such feuds between families in those parts: that he known many himself, with every circumstance attending them, and that they were very seldom finished until one family or the other was exterminated, and their names blotted out from the face of the earth.

Riley, “Sufferings in Africa”, Chapter XXII

By the time the shipmates were delivered unto the welcoming protection of William Willshire, Riley was a wreck of man. Normally weighing 240 pounds, he only weighed 90 lbs. at the time he was freed; and his exposed ribs had been “divested entirely” showing “white like dry bones”. This is why the maritime historian, Dean King, named his 2004 book, based upon Riley’s terrible two-month-long tribulation, “Skeletons on the Zahara”.

In order to understand the times in which we live, it is important to understand history. In so doing, the future becomes increasingly clear.

Upon Riley’s return to health, it was important for him to sit down again with Sidi Hamet to analyze exactly how it came to pass that the two men, formerly worlds apart, met upon the desert. In the penultimate chapter of “Sufferings in Africa”, Riley describes the two-year travels of Sidi, and his brother Seid, that led them to Riley and his men. It is quite a story and, therein, was a fascinating description of the early nineteenth-century Muslims who ventured further south, below the Great Sahara:

These true believers have very fine horses, and they go south to the country of the rivers, and there they attack and take towns, and bring away all the negroes for slaves, if they will not believe in the prophet of God; and carry off all their cattle, rice, and corn, and burn their houses; but if they will adopt the true faith, they are then exempt from slavery, and their houses are spared, upon their surrendering up one-half of their cattle, and half of their rice and corn; because, they say, God has delivered their enemies into their hands.

Riley, “Sufferings in Africa”, Chapter XXV

Also included in that chapter is an additional insight into the “Mohammedan mind” of the “good” Arab, Sidi Hamet, who helped to deliver Captain James Riley to freedom:

Though the free people in this place, do not steal, and are very hospitable, yet I hope the time is near when the faithful, and they that fear God and his prophet, will turn them to the true belief, or drive them away from this goodly land.

Riley, “Sufferings in Africa”, Chapter XXV

Yes, the times change with the tides; yet the tales, like the surf, sound on in familiar perpetuity and with steady repetition. In the modern era, during the great clash of civilizations currently underway, there will be no new, great and ghastly crusades. Only resistance or surrender. Although President Donald Trump now presides in America just as her tide recedes from the world; in the end it may, instead, become Man overboard, and every man for himself. The sun rises. The sun sets.

As sand through an hour-glass, or waves rolling over every shore, so too, do our journeys mark passageways through time; and, in the end, our navigation may, indeed, depend upon guidance, like stars, shining down from heaven upon what we know, over the decisions we make; on the destinies we choose.

And, of course, there will be losses incurred during the storms.

So, we raise our sails and pray for the prosperous winds of Providence to guide our ways and guard our lives through uncharted seas. Perhaps it’s true that fortune finds and favors the faithful above all. Even still, those who believe, and those who doubt, and those who sleep, all do drift and blow by the same breeze. The winds of change are on us. They’ve always been here, steadfast and old as time itself. Like the earth. Nothing new under the sun.

good article cola-you need to write more often-

LikeLike

I would like to, but research takes some time as well as the do the daily life responsibilities that are always calling. Writing helps me to release anger, face my fears, and it helps to keep me sober. Thanks for comment, T-red.

Uncola

LikeLike

“…waves of Islamic immigrants flood onto the shores of western nations like tsunamis.”

How many ways can we count that comment wrong.

One of the obvious ways, is to view it as a gross and irrational exaggeration.

You said that you had comments, representing 121 different countries on your blog, but I can’t even count 121 comments, period.

LikeLike

Seriously, Peter, your level of obtuseness is stunning. Only a very tiny percentage of readers comment. Just this morning people from these countries have visited this blog:

US

European Union (multiple)

Ireland

Canada

New Zealand

Denmark

Australia (21 views – probably all you)

Yesterday, included all of the above plus these nations:

Pakistan

Lithuania

Vietnam

Guam

Most readers, however, are courteous and respectful; including most of those who comment. Even those who do disagree, do so with substance, unlike you.

Instead, you are like the waves of islamic immigrants who flood the western nations like tsunamis.

https://www.express.co.uk/news/world/721626/Parisian-street-video-migrant-camp

Except instead of defecating in the streets of Europe, you have defecated on this blog for all to see. But only because I’ve allowed it for purposes of posterity.

Doug / Uncola

LikeLike